Health is a topic of discussion that needs more attention. The reality is, we are in a place where more education is available, and accessible so we can become more aware of the importance of our health and how to commit to your own health on a daily basis. Before we get more into the weeds of things, let’s connect the dots on the meaning of healthy. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines healthy as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”. Pretty complex, right. Question for you, are you healthy?

Some define healthy by their physical appearance, some by the balance they feel mentally or spiritually, but how many Black Americans can say they feel healthy as defined by the World Health Organization?

How many black individuals are proactive in taking an array of supplements to help support overall health and well-being?

As a critical care nurse, I have cared for patients that are experiencing the opposite of healthy. The healthcare team is there to treat the whole patient, not just the disease, with the understanding of how this acute change in health status affects the patient’s family and friends.

Keeping with the idea of physical health, Black Americans are getting healthier and living longer. There are black health facts and statistics to note, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the death rate for Black or African-Americans has declined about 25% from 1999 – 20151. However, chronic diseases among Black Americans are still higher than our White counterparts. The CDC states that Black Americans ages 18-49 are 2 times as likely to die from heart disease and 50% more likely to have high blood pressure than Whites. Why is that? Well, in thinking about my own family, food was a big part of our family gatherings – Sundays at my auntie’s house for her amazing fried chicken, summer BBQs at my uncle’s house where he sometimes roasted a whole pig – looking back, I don’t remember seeing a lot of salad or grilled vegetables at those family gatherings. As an adult, when I tried to incorporate healthier alternatives during those family gatherings I would sometimes get strange looks from my family. The one healthier alternative that stuck was to replace ham hocks with smoked turkey legs in our collard greens. I would imagine, many can relate to the same type of experience.

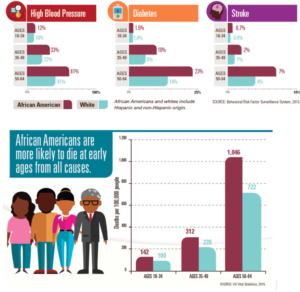

High blood pressure, or hypertension; diabetes, and stroke are disease states that can be managed through diet and exercise. Key in the diet discussion at family gatherings, right? Now, we can’t always account for our genetics but if you know and understand your risk factors for certain health conditions, you can make changes early to mitigate some of the complications that arise from these chronic health conditions.

In the diagram from the 2015 US Vital Statistics and the 2015 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Systems, you can see that Black or African Americans have a higher incidence of high blood pressure, diabetes, and stroke once they reach age 50 – 64. 1046 per 100,000 people with diabetes are Black Americans ages 50 – 64. This is the age when chronic diseases are usually diagnosed. So, does this tell us that Black Americans are not making changes early enough in life?

Why aren’t Black Americans making lifestyle changes early in life? Are we truly not recognizing our risk factors? Or are we even able to make lifestyle changes early? Are we able to access preventable medicine?

Health disparities in the Black American community reached its peak during the coronavirus pandemic. COVID-19 exposed the dark and dirty truth that non-Whites do not have the same access to healthcare and healthy foods.

Black Americans, as a whole, are taught to not trust “the system”. We don’t see a lot of healthcare practitioners that look like us, speak like us, or seem to understand our barriers and struggles. This adds to an almost inevitable mistrust of the healthcare system. We can look back at the Tuskegee airmen experiment and the story of Henrietta Lacks, but most recently, look at what happened during the coronavirus pandemic. With the push to vaccinate as many people as quickly as possible, vaccination clinics across the Commonwealth of Massachusetts started offering the Janssen vaccine by Johnson & Johnson. As a healthcare practitioner, it made sense – this vaccine provides 85.4% efficacy against severe disease and 93.1 % against hospitalization 28 days after inoculation2. The Janssen vaccine provides protection in one shot versus two and it doesn’t require the same extreme temperature for storage as the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines. However, with the ease of inoculation came side effects. When the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) decided to pause inoculations of the Janssen vaccine, there were six reported cases of women that developed blood clots thought to be associated with the vaccine, one woman died. Six out of 6.8 million shots given nationally as of April 12, 2021, is a very small number. You probably have better odds of hitting the lottery! After a meeting of an advisory panel at the CDC, the pause ended, and a warning label about the potential for an uncommon, but potentially serious blood clotting disorder would be added to the vaccine.

Interestingly enough this was the vaccine that was touted to the inner cities and “hard to reach” communities of Massachusetts. There were programs where paramedics and EMTs were even making house calls to vaccinate home-bound individuals with the Janssen vaccine. For a group of people that already didn’t trust the healthcare system, how does this seem right? A slightly less effective vaccine that could potentially cause a serious blood clotting disorder is being offered to our most vulnerable populations. The CDC deemed the Janssen vaccine safe but there is still a lot of skepticism from the public. States across the country had different vaccine rollout programs. In Massachusetts when the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines were approved for emergency use, the first to get these were first responders, health care workers, and residents of nursing homes. When the general public became eligible, the Janssen vaccine had also received emergency use authorization. Some groups felt slighted.

“Why can’t we get what the doctors and nurses got?”

“Why are we getting the less effective vaccine?”

“Is our health not as important as the nurses, doctors, and first responders?”

When in fact, the choice to offer the Janssen vaccine came down to logistics – it’s a one-shot vaccine that is easy to transport and easy to store. Try to convince a group that is already skeptical of the healthcare system that this choice was purely based on logistics. Some of our most skeptical groups of immigrant backgrounds spoke of beliefs that tracking devices were put into the vaccines to help the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) agents find undocumented individuals to deport them. Imagine the fear for your life and your place of residence.

I state all of this because, as a people, Black Americans need to ask questions and keep asking questions, and if you are not satisfied, continue to ask more questions. Black Americans should focus on considering the source of the information. There are safeguards in place to prevent another Tuskegee Airmen experiment and more Henrietta Lacks stories. Black Americans that do trust “the system” need to educate those in their community that does not and show through their actions that the healthcare system is a safe place. Black Americans cannot continue to suffer from preventable and manageable chronic diseases because of a lack of trust. We must recognize our barriers and learn to navigate them.

My recommendations to attain a healthy state as defined by WHO is:

- Eat a balanced diet. Always incorporate fruits and vegetables into every meal.

- Avoid “fad” diets

- Look for diets that incorporate all the food groups into a personalized meal plan. Not everyone eats the same foods.

- Be active for at least 30 minutes per day

- Don’t run out and get a gym membership if you’ve never gone before. Start slow. Walk around the neighborhood, on a bike/walking path, along the beach.

- Take a daily multivitamin

- See your primary care doctor on a regular basis. It’s important for them to see you when you’re healthy, not just when you’re sick.

- Have an open and honest discussion with your primary care doctor about your health goals.

- Meditation is a great way to achieve mental health.

- Tend to your spirit, whether that be through religious activities or community activities. Do intentional things that make you feel good.

Lastly, mental health comes with stigma and as society attempts to break the stigma, it is still very present. If you suffer from disorders and conditions that affect your mental health – addiction, depression, anxiety, to name a few – see a mental/behavioral health specialist on a regular basis. Mental health is just as important as physical health.

Here are a few organizations I like to follow, and I feel provide some great information for Black Americans:

- The African American Wellness Project – https://aawellnessproject.org/?gclid=CjwKCAjww-CGBhALEiwAQzWxOvRcwYvF1eQH4MyD4T34dsE5a40yMF-jSPINicSIasgJX3RIsC6TmhoCG1YQAvD_BwE

- The Health and Human Services, office of minority health – https://www.minorityhealth.hhs.gov/

- Black Girls Run Foundation – https://blackgirlsrun.com/bgr-foundation/

- African American Health: Creating equal opportunities for health. (2017). Centers for disease control and prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/aahealth/index.html

- The Janssen Ad26.COV2.S COVID-19 vaccine: What you need to know. (2021). The World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/the-j-j-covid-19-vaccine-what-you-need-to-know?gclid=CjwKCAjww-CGBhALEiwAQzWxOgvh9Q3L5iqfe79973Kk8EDnQJzv-rHjJZ9ufg9UAwGm1tEMfj0z1RoC8K8QAvD_BwE 3

- Katella, K. (2021). The Johnson & Johnson vaccine and blood clots: What you need to know. Yale Medicine. https://www.yalemedicine.org/news/coronavirus-vaccine-blood-clots

Author Bio:

Tiffany Diaz Bercy, RN, MSN, CCRN is an intensive care clinical staff educator at a 400-bed hospital in a community north of Boston, MA. Tiffany has been a nurse for over 20 years with more than 18 years of experience in critical care.